For several months now, I’ve been meaning to post to this blog an entry about Docker. My primary tasks within the HP Advanced Technology Group over the last few months have been to research both Docker and Ansible. I hope this post will serve to provide some basic understanding and context for the Docker project in particular, and set the foundation for future posts on the work I’ve been doing.

What are containers and how do they work?

The first thing in discussing Docker would be to explain its most basic component, the container.

A container is an operating-system level virtualization method that provides a completely isolated environment, simulating a closed system running on a single host. It gives the user the ability to have an environment to do whatever is needed; in particular develop and run applications with the necessary resources and environment configuration.

There are numerous types of container mechanisms and technologies such as chroot, OpenVZ, Parallels, FreeBSD Jail, Linux Containers (LXC), and libcontainer, which is the default execution environment.

The basic idea of a container is to contain a process or set of processes such that they appear to have their own PID and are not visible outside of the container. This also means networking, users, disk, and other aspects that make an environment usable. This isolation is made possible on Linux using a number of kernel features: kernel namespaces (network, user, IPC, uts, PID, and mount), cgroups, Apparmor/SELinux profiles, and secomp policies.

What is Docker?

Docker is developed by Docker.inc (formerly DotCloud), the corporate entity behind the Docker project. As described on the website, Docker is a “an easy, lightweight virtualized environent for portable applications”. To elaborate, Docker is an application the extends containers (as opposed to virtual machines). Specifically, its value is that is makes it incredibly easy to manage containers and that it makes it possible to deploy applications in manageable units that can run anywhere. The days of having to deal with the hassle of application dependencies across various Linux variants or even different types of virtual machines or hardware are now made trivial. With Docker, you can build your application in a container that runs on your laptop or on a virtual machine and be assured that it can also run in any environment. This truly is revolutionary in terms of software development, testing and deployment.

Docker consists of: (1) a daemon with a RESTful API (2) Docker command line interface. This CLI also includes the ability to search and “pull” images from both (3) public and private Docker image registries.

What is the difference between containers and virtual machines?

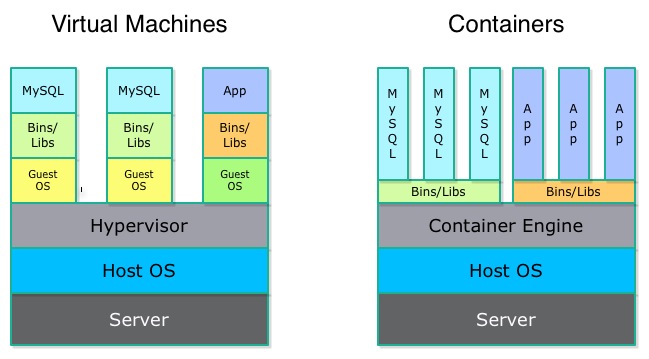

One of the first questions that is often asked, especially considering the prevalent use of virtual machines (VM) is “what is the difference between virtual machines and containers?”. The answer is: a virtual machine requires some sort of emulation layer or hypervisor complete with an OS installation for each VM whereas a container uses features in the Linux kernel (3.x) to provide an isolated virtual environment– disk, memory, networking, etc., on the same OS. Containers use the OS in question and do not require an install of anything other than the files required for your application.

If you consider your application in terms of what files on disk it requires as well as considering what processes are required when instantiated using a container, you will realized that containers need far less less disk space and memory than is required to run on a virtual machines with all of its own resource prerequisites.

The next question that is commonly asked: which of the two is better? The answer is: neither. It really depends what you are trying to do – each has its purpose. Sometimes, a virtual machine is needed to provide an environment that is satisfied with a full, complete OS installation and other associated functionalities. However with other applications, where developers wish to ship the application – either to a testing group or even a customer– as a single unit, something like Docker will fit the bill.

One other use case for a virtual machine: to run Docker on, particularly on non-Linux OSs!

Why Docker?

Why would you want to use Docker? My experiences in using it have lead me to the following conclusions:

Docker is Fast!

I was very accustomed to thinking in terms of virtual machines; whether it was running VMware on a laptop with a development virtual machine for my various projects or working on various platform service applications that required automation and provisioning of numerous virtual machines on HP Cloud (Nova).

Particlarly with automation of virtual machines on the cloud, testing deployments using either Chef or SaltStack became an exercise in watching paint dry as you waited (and waited) for a run to finish before you could start to see how the application as a whole responded.

When I first started investigating Docker, I would provision numerous containers to get a feel for how it worked with either SaltStack or Ansible. The thing that struck me the most was how fast launching containers is. Since a container don’t require an OS installation, time isn’t consumed booting an OS. A container consists of only the files and processes that an application requires, so launching a container only takes however long your application needs to start.

Docker is simple

Docker is very simple to install, configure, and use. Their installation page covers installing Docker on any number of Linux variants as well as other OSs using virtual machines.

Once Docker is up and running, pulling images from the public Docker image repository is a snap. You can then quickly deploy containers, make changes and create your own images, and, another swath of icing on the cake, push up your images to share with others on the public Docker image registry.

The Docker command-line tool is simple to use, intuitive and offers plenty of help for the numerous sub-commands.

Docker is a great tool for developers

Virtual machines have always been useful to me for doing local development work on a workstation or laptop. I usually end up setting up my virtual machine in a very particular way and hesitate to modify it or do something that might jeopardize how it’s set up. If I have to create a new virtual machine, I have to go through the motions of installing the OS and setting up the virtual machine set up with all the tools and environment I often customise to some degree. I have found since using Docker, that containers are much more “disposable” than the virtual machines I use and that I know that I can always rebuild much faster than with a virtual machine. Plus, containers take far fewer resources both in terms of disk and memory. I can run more of them and keep more images on disk than I would with a virtual machine.

One might ask “why not just use the cloud?”. While that is one possible solution as opposed to having to run virtual machines locally, sometimes I would prefer to not have to run things externally, requiring using a metered account that requires a remote connection to do simple developmental tasks. Docker solves the need to have a quick environment ready to use and dispose of. Additionally, I can commit images along the way, allowing me to have any number of images representative of the iterative state of changes made to my environment at any given point in time.

Docker works well and has plugins for the varous automation tools

Because of Docker’s popularity, developers of automation tools have written plugins and functionality for Docker:

- Ansible

- docker module

- docker_image module

- docker dynamic inventory plugin

- SaltStack - salt.states.dockerio

- Puppet - gareth-docker module

- Chef - Chef and Docker

Terminology: Containers and Images

Correct terminology is important in discussing technology. For me, I still will slip and say “instance” when I mean “container” because my experience has been working with virtual machines up until recently.

With Docker, an incredibly useful feature is the ability to easily create Docker images from running containers. These are the read-only component, which can also be though of as templates for Docker containers. When run, they become a given container, the writeable component.

When using Docker, you start out with a base image which is your starting point in building derived images. An image you create from a running container, each time you commit, is comprised the “deltas”, so to speak. An usage pattern would be that you might start out with a simple base image that contains a stock Linux environment. Then install a web server, along with your application. When the container reaches a running version of your application you would then commit that container as an image. Each change commit (“delta”), is given a unique 256-bit ID (64 hex characters). Subsequent commits are given their own IDs and Docker provides a way to view an image and see its history and have a hierarchical view of the image.

Since containers only require the files specific to that applicaiton (code, libraries, etc) and are defined by specific processes versus an entire OS and its processes, they require far less disk space and fewer resources. Therefore it is possible to have on disk many more images and run many more containers than VM technology would accomodate.

One can use the Docker CLI to search for any number of images to use as-is or to modify and build images from.

Next installment: Installing and configuring Docker

As I mentioned before, there is a lot about Docker that is worth discussing. I plan to be posting here in the next week a series of blog posts about Docker. The next blog post will cover installation and configuration of docker. Stay tuned, and do feel free to ask questions!